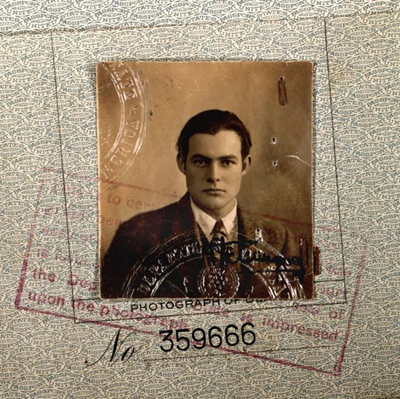

Passport photo of a young Ernest Hemingway when he was living in Paris in the 1920s. His memoir, the Moveable Feast, describes those days.

Ernest Hemingway saunters into his namesake restaurant, Hemingway’s on Pensacola Beach in Florida, and orders a bowl of gumbo and a glass of white wine. The server, a blonde coed no way resembling the mustachioed men who waited tables in the Paris cafes in 1920, places the entrée on the table. Hemingway tastes the gumbo and slides the bowl away — it’s not to his liking.

After reading the restored edition of The Moveable Feast edited by Hemingway’s grandson, there’s no doubt the famous writer would shove away Caribbean-spiced gumbo. It’s missing a key ingredient he loved. In fact, he penned the most famous sentence in literature about the missing ingredient . . .

“As I ate the oysters with their strong taste of the sea and their faint metallic taste that the cold white wine washed away, leaving only the sea taste and the succulent texture, and as I drank their cold liquid from each shell and washed it down with the crisp taste of the wine, I lost the empty feeling and began to be happy and to make plans.”

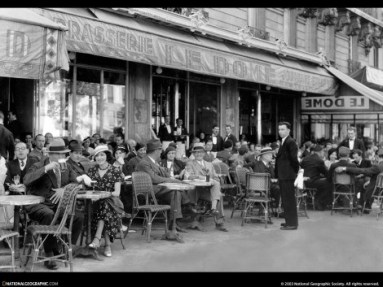

On that occasion Hemingway devoured a dozen portugaises, the inexpensive oyster available in Paris in the 1920s. Legend has it that the oblong portugaises (Crassostrea angulate) descended spontaneously from the sinking of a single oyster-laden ship from the orient in a harbor in Portugal.

Later when poet Ernest Walsh was footing the bill at the best and most expensive

restaurant on Paris’ Boulevard St.-Michel, Hemingway feasted on the expensive, flat faintly coppery marennes. . .

“I began my second dozen of the flat oysters picking them from their bed of crushed ice on the silver plate, watching their unbelievable delicate brown edges react and cringe as I squeezed lemon juice on them and separated the holding muscle from the shell and lifted them to chew them carefully.”

So, if the ghost of Hemingway drops by your place, serve him seafood gumbo laden with oysters – and a bottle of cold, white wine. And hand him a pen and paper because if he can describe an oyster like that, his description of seafood gumbo will surely make you weep.

Note: This entry is the second post in a 52-part series on American Writers and their gumbo choices. To learn more about Hemingway and oysters, visit

Hemingway Oyster Aficionado: Legends True or Not

Thanks, Diane for bringing such a rich menu of writing, writers, and great recipes. This new project with famous authors is very special and rare; I know many will find expanded understanding about their favorite authors, and about living life to the fullest!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for reading. Next week I’ll feature Mark Twain and his favorite — as usual with Twain there’s a rich story to accompany the choice.

LikeLike

What’s most amazing to me is that Hemingway’s descriptions of those dishes seem so verbose in comparison with his fiction-writing style!

I prefer William Faulkner’s writing to Ernest Hemingway’s–and the two had a not-so-friendly rivalry regarding their opposite-pole writing styles.

Of Faulkner’s writing, Hemingway said, “There’s gold there, but you’ve got to wade through a lot of crap to get to it!”

Faulkner retorted, “Ernest Hemingway never uses a word for which you have to refer to a dictionary to get its meaning!”

LikeLike

I love this! And you’re right, it does seem verbose for Hemingway and his Kansas City Star newspaper style. I heard once that Faulkner penned the longest sentence in American literature in his short story, “The Bear.” Thanks for reading.

LikeLike